Here are some thoughts about praying the Psalms from Eugene Peterson.

"If we want to pray our true condition, our total selves in response to the living God, expressing our feelings is not enough — we need a long apprenticeship in prayer. And then we need graduate school. The Psalms are the school. Jonah in his prayer shows himself to have been a diligent student in the school of Psalms. His prayer is kicked off by his plight, but it is not reduced to it. His prayer took him into a world far larger than his immediate experience. He was capable of prayer that was adequate to the largeness of the God with whom he was dealing.

This contrasts with the prevailing climate of prayer. Our culture presents us with forms of prayer that are mostly self-expression — pouring ourselves out before God or lifting our gratitude to God as we feel the need and have the occasion. Such prayer is dominated by a sense of self. But prayer, mature prayer, is dominated by a sense of God. Prayer rescues us from a preoccupation with ourselves and pulls us into adoration of and pilgrimage to God. Pastors, who are vocationally immersed in so much experience — people throbbing with pain, panicked in crisis, mired in confusion — are in particular need of such rescue.

For there is no lack in us of the impulse to pray. And there is no scarcity of requests to pray Desire and demand keep the matter of prayer before us constantly. So why are so many lives prayerless? Simply because “the well is deep and you have nothing to draw with.” We need a bucket. We need a container that holds water. Desires and demands are a sieve. We need a vessel suited to lowering desires and demands into the deep Jacob’s Well of God’s presence and word and bringing them to the surface again. The Psalms are such a bucket. They are not the prayer itself but the most adequate container, askesis, for prayer that has ever been devised. Refusal to use this psalms-bucket, once we comprehend its function, is willfully wrongheaded. It is not impossible, perhaps, to construct a container of a different shape and material that will serve makeshift. It has certainly been done often enough. But why settle for such as that when we have this magnificently designed and spaciously proportioned container given to us and at hand?

For eighteen hundred years virtually every church used this text. Only in the last couple of hundred years has it been discarded in favor of trendy devotional aids, psychological moodbenders, and walks on a moonlit beach.

The Psalms, of course, are not “devotional,” or “psychological,” or “romantic.” They are no use at all to us in any of these departments. Their use is as an element of askesis, a form for our formlessness.

The fundamental ascetic form — and this is the church’s consensus for two thousand years — is the Psalms prayed daily in sequence each month.* (This is the “office” of the Roman Catholic, the Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican, and for the rest of us, the Psalms divided into thirty segments and prayed through monthly, whether we feel like it or not.)"

-Excerpts from Under the Unpredictable Plant by Eugene H. Peterson

*Or weekly, following the Rule of St. Benedict which states: “We especially impress this, that, if this distribution of the psalms should perchance displease anyone, he arrange them if he thinketh another better, by all means seeing to it that the whole Psalter of one hundred and fifty psalms be said every week...[lest] those monks who show too lax a service in their devotion in the course of a week, chant less than the whole Psalter with is customary canticles; since we read, that which our holy forefathers promptly fulfilled in one day, we lukewarm monks should, please God, perform at least in a week.”

"If we want to pray our true condition, our total selves in response to the living God, expressing our feelings is not enough — we need a long apprenticeship in prayer. And then we need graduate school. The Psalms are the school. Jonah in his prayer shows himself to have been a diligent student in the school of Psalms. His prayer is kicked off by his plight, but it is not reduced to it. His prayer took him into a world far larger than his immediate experience. He was capable of prayer that was adequate to the largeness of the God with whom he was dealing.

This contrasts with the prevailing climate of prayer. Our culture presents us with forms of prayer that are mostly self-expression — pouring ourselves out before God or lifting our gratitude to God as we feel the need and have the occasion. Such prayer is dominated by a sense of self. But prayer, mature prayer, is dominated by a sense of God. Prayer rescues us from a preoccupation with ourselves and pulls us into adoration of and pilgrimage to God. Pastors, who are vocationally immersed in so much experience — people throbbing with pain, panicked in crisis, mired in confusion — are in particular need of such rescue.

For there is no lack in us of the impulse to pray. And there is no scarcity of requests to pray Desire and demand keep the matter of prayer before us constantly. So why are so many lives prayerless? Simply because “the well is deep and you have nothing to draw with.” We need a bucket. We need a container that holds water. Desires and demands are a sieve. We need a vessel suited to lowering desires and demands into the deep Jacob’s Well of God’s presence and word and bringing them to the surface again. The Psalms are such a bucket. They are not the prayer itself but the most adequate container, askesis, for prayer that has ever been devised. Refusal to use this psalms-bucket, once we comprehend its function, is willfully wrongheaded. It is not impossible, perhaps, to construct a container of a different shape and material that will serve makeshift. It has certainly been done often enough. But why settle for such as that when we have this magnificently designed and spaciously proportioned container given to us and at hand?

For eighteen hundred years virtually every church used this text. Only in the last couple of hundred years has it been discarded in favor of trendy devotional aids, psychological moodbenders, and walks on a moonlit beach.

The Psalms, of course, are not “devotional,” or “psychological,” or “romantic.” They are no use at all to us in any of these departments. Their use is as an element of askesis, a form for our formlessness.

The fundamental ascetic form — and this is the church’s consensus for two thousand years — is the Psalms prayed daily in sequence each month.* (This is the “office” of the Roman Catholic, the Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican, and for the rest of us, the Psalms divided into thirty segments and prayed through monthly, whether we feel like it or not.)"

-Excerpts from Under the Unpredictable Plant by Eugene H. Peterson

*Or weekly, following the Rule of St. Benedict which states: “We especially impress this, that, if this distribution of the psalms should perchance displease anyone, he arrange them if he thinketh another better, by all means seeing to it that the whole Psalter of one hundred and fifty psalms be said every week...[lest] those monks who show too lax a service in their devotion in the course of a week, chant less than the whole Psalter with is customary canticles; since we read, that which our holy forefathers promptly fulfilled in one day, we lukewarm monks should, please God, perform at least in a week.”

Steps to Praying the Psalms

Praise the LORD!

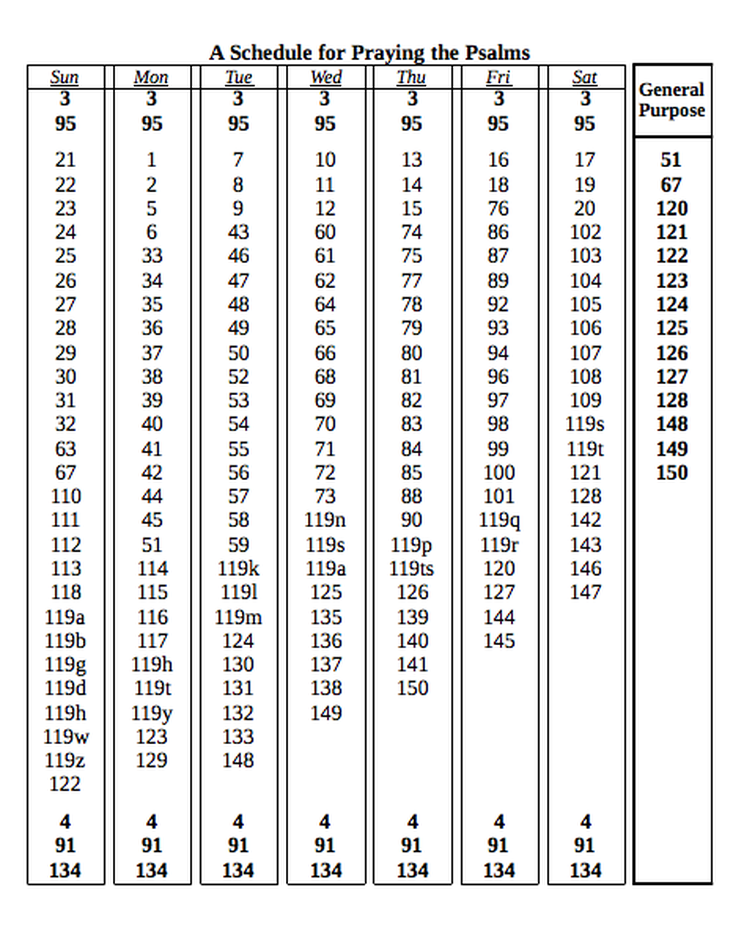

A Few Explanations About the Schedule

*The bolded Psalms at the top of each day's column are to read when you wake up and the bolded Psalms at the bottom of each day's column are to read right before you go to sleep.

*The rest of the Psalms in each day's column are to read at some point during that day of the week - either in a few chunks or all at once (all at once will take about an hour).

*The General Purpose Column is for when you feel led to pray the Psalms apart from the routine you have been following.

- Respond to the call to pray. This call to pray may be prompted from a reading of scripture, a specific invitation to a time of prayer, or in response to a situation that desperately needs prayer.

- Recognize the power of praying the Psalms. Join with Jesus, Jonah, Augustine, Ambrose, Benedict, Bonhoeffer, and countless others in praying this ancient manner.

- Accept a rule. This can be a particular set of Psalms to read, such as a daily office, or it can be a given amount of time to pray. There is power in humbling ourselves to obedience.

- Move your lips. This monastic criteria is based on the Rabbinic requirement that prayer must involve moving lips, derived from the story of Hannah in 1 Samuel 1:12-13 and the nature of the Hebrew verb hagah. Prayer doesn't have to be projected though, you need only to make enough sound for you and the Holy Spirit to hear.

- Pray the Psalms. This is not merely reading the Psalms aloud, but making the words of the Psalms your own. Reflect on how they apply to your life. Consider these things:

- Many psalms talk about enemies. Think about what enemies you face. Are they physical infirmities? Specific people? Demonic forces? Spiritual problems? Emotional difficulties?

- There is frequent mention of suffering. Consider how these Psalms apply to Jesus. Compare the ways you suffer to His life on earth and death on the cross. Remember the power He demonstrated over pain and death. Think of the persecuted church around the world, and throughout time, and pray these psalms in intercession for them. Remember that throughout history praying the psalms have helped the faithful flourish under oppression. Or perhaps there is someone else whose suffering is particularly poignant to you. Pray these psalms for them. See how the power of the Gospel can apply to them.

- Many psalms refer to Biblical history. Think of yourself as a continuation of those stories, for you are!

- And finally, many psalms praise God, and call on us to praise God. Let us also praise God. Let everything that has breath praise the LORD.

Praise the LORD!

A Few Explanations About the Schedule

*The bolded Psalms at the top of each day's column are to read when you wake up and the bolded Psalms at the bottom of each day's column are to read right before you go to sleep.

*The rest of the Psalms in each day's column are to read at some point during that day of the week - either in a few chunks or all at once (all at once will take about an hour).

*The General Purpose Column is for when you feel led to pray the Psalms apart from the routine you have been following.

-Abraham

RSS Feed

RSS Feed